Byline: Space & Science Correspondent

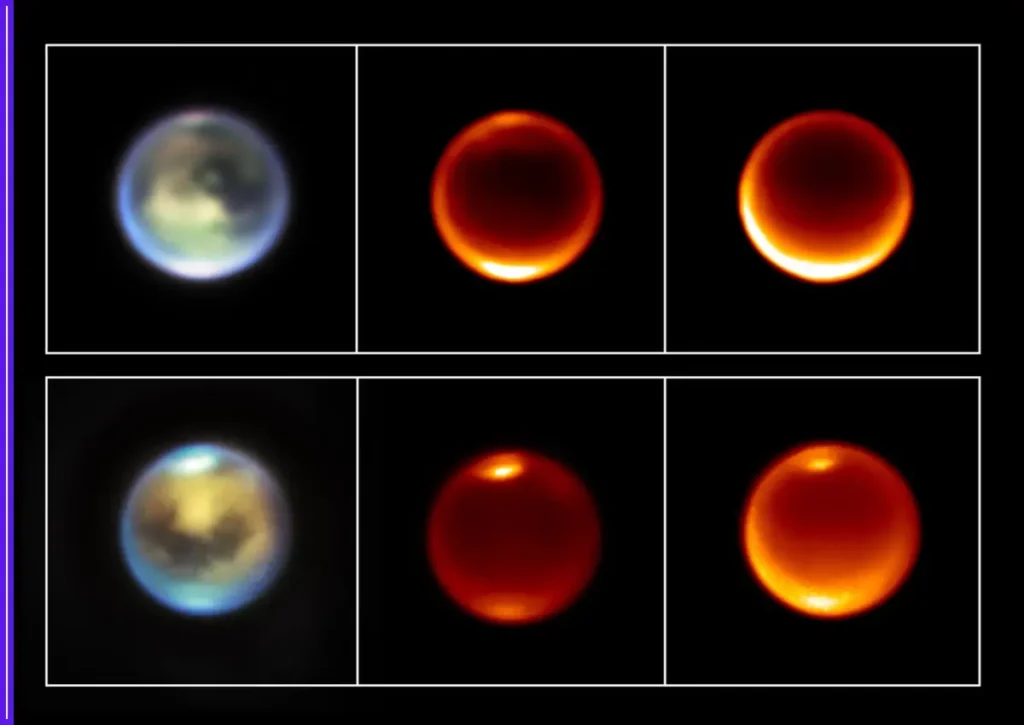

In a groundbreaking development, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has delivered the first-ever visual evidence of methane cloud formations swirling in the northern hemisphere of Titan — Saturn’s largest and most Earth-like moon.

This discovery marks a pivotal moment in our understanding of Titan’s climate dynamics. While previous missions, including the legendary Cassini–Huygens, had observed clouds in Titan’s southern hemisphere, its northern skies had remained mysteriously clear — until now.

According to NASA, the JWST captured the images during Titan’s northern summer, a season astronomers had long speculated might stir up atmospheric changes. What the telescope saw confirmed that suspicion: billowy methane clouds forming in a pattern that suggests an active and evolving weather system.

“Titan is unlike any other place we know,” said Dr. Conor Nixon, a planetary scientist with NASA. “To finally observe clouds forming over the methane-rich lakes and seas of the north is not just fascinating — it’s transformational.”

The methane clouds, much like water clouds on Earth, are believed to form through convective processes, where warm gas rises, cools, and condenses. This observation hints that Titan’s methane cycle — which includes cloud formation, rainfall, and surface pooling — could be even more Earth-like than previously imagined.

Adding further credibility to the findings, the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii independently confirmed the cloud formations shortly after JWST’s initial capture. This dual confirmation showcases the immense value of pairing powerful space telescopes with Earth-based observatories.

Until now, Titan’s northern hemisphere had been somewhat of a meteorological mystery. Despite hosting vast methane seas, it showed little atmospheric activity in the past. JWST’s ability to peer deeper into the infrared spectrum made it possible to penetrate Titan’s dense haze and reveal this atmospheric transformation.

Why It Matters

Titan is one of the few places in the solar system known to host liquid on its surface — not water, but liquid methane and ethane. These conditions have made Titan a key target in the search for environments that could support prebiotic chemistry, or even primitive life.

The discovery of northern cloud activity not only validates long-held theories about seasonal weather on Titan but also strengthens its profile as a candidate for future exploration. NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission, a rotorcraft lander expected to launch later this decade, could benefit greatly from this new data in planning its descent and study sites.

As the James Webb Space Telescope continues to unlock new secrets of the cosmos, its gaze toward our own solar system is proving just as valuable. Titan, it seems, is no longer the quiet giant we once thought — it’s very much alive with change.